Programming seems to be a field in which everything is complicated and “depending on the situation”. Even the simplest problems don’t have one best solution (try asking on Twitter “which framework is the best to make a ToDo app” and watch the thread burn 😋). How can you learn anything in such an indecisive environment? How can you decide which rules and advice you should follow if every one of them got as many arguments for as against?

Well, one thing you can do is to build your base of knowledge on such rules that are ubiquitous, regardless of the situation (well, let’s say, 99% of the situations). A good example of what I’m talking about is the book “Clean Code” written by George R. Martin Robert C. Martin. Following a previous example, if you write on Twitter ”Is it good to use rules from the book “Clean Code”?” you’ll only get replies like “Of course. Everyone knows that.”. But how many such solid rules are there in programming?

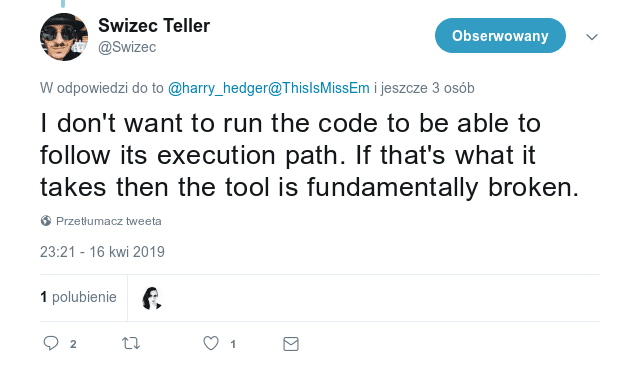

Other programmers, which I follow, also try to describe some universal rules of creating good software: for example Kent, Swizec, or Mark.

Well, I have also created one rule, which I haven’t seen described in any blogs or books:

Avoid implicit coupling in the code

First, some definitions:

What is implicit coupling?

Dependency between two code pieces is a situation in which one of them needs the second to run.

Coupling refers to how the functions are related to each other. I’ll be using this word for naming the exact thing that makes one code dependent on other. It’s divided into explicit and implicit.

Consider this simple program that prints the multiplication of two numbers in the browser console:

function printMultipliedNumbers(first, second) {

let result = myMathOperation(first, second);

console.log(result);

}

function myMathOperation(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

printMultipliedNumbers(2, 4);We can clearly see that the function printMultipliedNumbers is dependent on the myMathOperation. In order for the first function even run, the second function must:

- exist (be callable by this specific name)

- accept two arguments

This is explicit coupling and any decent IDE will show you that automatically (here is an example of a “peek definition” option in code sandbox):

But there are more couplings in our code example - arguments passed to the myMathOperation function must be numbers (for example, you can’t pass strings like "one" and "two"). Otherwise it would not be able to multiply them. That’s also a coupling, and what’s worse, it’s implicit. There is no automatic mechanism that could figure out and help you remember that (or ensure integrity in the future). Every time someone else (or you in the future) would want to use this function, he have to take a look at what’s inside of it. Every time he would want to modify it, he have to find all usages of it to make sure that he didn’t break any of the implicit couplings imposed by other programmers. And if you use a language like Javascript, you can’t even rely on your IDE to find all usages of that function. You will never know if someone else uses your function and will have his code broken due to your changes.

We can depict dependency and coupling using sets:

Dependency is a situation in which the red set exists. Coupling is a measure of how big it is – propability that after changing A we should also change B. And how many different modules can be affected after changing A (there could be more “red sets” inside the blue one):

We can break a red set into two complementary subsets - one would be explicit coupling and second implicit coupling (so the new set is: changes in A, which require change in B to still be correct, but aren’t, necessary for program to run):

How to avoid it?

1. Use type system and static code analysis

Some of these couplings could be moved from implicit to the explicit domain using a type system. Just use Typescript and write:

function myMathOperation(a: number, b: number): number {

return a * b;

}And everyone will know that this function accepts only numbers. If someone would like to modify it to accept strings, he would get a compilation error saying that it will break the function printMultipliedNumbers. This way we can move some of our couplings from the implicit to the explicit domain by using type system, which enables more static code analysis. “Peek definition” option seen before is an example of static code analysis - it’s a set of powerful tools that aim to give a programmer as much information about couplings as possible basing on the type system and other programming language features. In languages without strong type system your only alternative to this is manually checking all this information every time you want to write any code. In small projects it isn’t any problem (it takes usually one glance at the function definition, like in our example), but as the project grows it starts taking more and more time.

2. Use tests

Those were requirements to merely execute the first function. To make it work properly we still have more assumptions to be fulfilled. We have to be sure that myMathOperation returns the multiplication of two numbers given as arguments. That’s also a coupling. And what’s worse, it’s impossible to build any automatic mechanism that could figure it out (because it’s not part of the programming language. That’s your ‘business’ requirement and only you know that it should work like that). There is a mechanism, but it’s not automatic. It’s called testing and can look like that:

function isMyMathOperationDoingWhatIWant() {

return (

myMathOperation(0, 1) == 0 &&

myMathOperation(1, 2) == 2 &&

myMathOperation(2, 3) == 6

);

}So you just have to write down a requirement that you have in your head in the form of an executable function. It’s not part of your main program, but you can execute it regularly to check that no one changed your myMathOperation function in a way that would break your assumptions about it (and introduce a bug in your function). This way we can move some of our couplings from the implicit to the explicit domain by using unit tests.

More examples

Now, when the basics are introduced, I’ll show some real-world examples that I often encounter during my work. Consider typescript function which sends api request to the backend to get some data:

function getDataForFilters(): any {

return restService.get("../MVC/Data/GetData/GET_DATA_FOR_FILTERS");

}

function getSearchFiltersData(): any {

let anyObject = getDataForFilters();

if (anyObject.Status === 1) {

return {

data: anyObject.Data,

types: anyObject.Type

};

} else {

displayGenericError();

}

}I stumbled upon this function during resolving some bug and it was important for me to get to know what data comes in response. Unfortunately, there was no “peek definition” functionality that I could use (the coupling is implicit, address string is the only trace of it). To achieve it, I had two options:

- run the program and visualize in a debugger what values are in a variable

anyObject - open the backend project and find the function that was sending a response to this request

Both options are unnecessarily bothersome and prone to error. The best solution to this problem is if you have that backend function written in the same language, you can make a shared type that would define the shape of the data both in the function that sends it and function that receives it. This way you will introduce new, explicit dependency (both functions will be dependent on this shared type), but if you won’t introduce explicit coupling, the implicit one will still be there, just harder to work with in the future. There is no such thing as “perfectly decoupled components”. In the end, when you change one of it, other one will stop working as it should.

Here’s the code that gets rid of this implicit coupling:

type DataForFilters = {

Status: number;

Data: string;

Type: number;

};

function getDataForFilters(): DataForFilters {

return restService.get("../MVC/Data/GetData/GET_DATA_FOR_FILTERS");

}

function getSearchFiltersData(): { data: string; types: number } {

let anyObject = getDataForFilters();

if (anyObject.Status === 1) {

return {

data: anyObject.Data,

types: anyObject.Type

};

} else {

displayGenericError();

}

}As you can see, in Typescript you can make the dependency on the data shape explicit by simply avoiding use of the any type. In the above example, DataForFilters type would have to be used also to define the shape of data that is sent from the backend and you will be safe from any unnoticed changes.

other examples

Eiffel programming language does great work with its “design by contract” approach. Each routine has information included in its definition about what must be true before a routine is executed (precondition) and what must hold to be true after the routine finishes (post-condition) (source). Strong type systems are great in making coupling visible, and it’s more deep topic than just “specifying argument types”. Functional languages are also doing great job in avoiding implicit coupling by not mutating variables and not using side effects. Pure functions by definition can’t have any implicit dependencies - they are dependent only on calling arguments and other functions can be dependent only on it’s returned value. I believe it gives great advantage, but I haven’t seen anyone mentioning this feature in any FP-OOP discussions.

Conclusion

When you omit writing down assumptions that make your code coupled with other code, you create unmaintainable system in which people are afraid to make any change, because they literally don’t know what will happen if they change it. The only reason I know for which people are doing this is just that it’s a little bit faster. In some of the languages (like Javascript) it is in fact very hard and time-consuming to describe all these assumptions, which people use as a good excuse to not bother about it.

But hey - you can change the language. At first glance, it can look like the code in weak typed system is less coupled, because you don’t see the coupling, or, you don’t have a compiler screaming at you. In fact, you just change your explicit couplings into implicit ones and this is a bad deal.

It’s reasonable to avoid having big coupling, because then even small change in the codebase could imply a cascade of other changes. We don’t want to spend a lot of time on every small change. But if you reduce explicit coupling just by making it implicit, you trade situation in which:

- After one change in codebase you have to repair 20 another pieces of code (big coupling)

For situation in which:

- After one change in codebase 20 bugs appear. Some of them you’ll guess and correct, some will be caught in tests and rest will go to production. (equally big coupling, but implicit)

Implicit coupling is the reason why in big and old software a simple change or bug fix can take 8 hours instead of 10 minutes. Or a reason why after one month of introducing changes and new features, you have to test and fix them for a whole next month, because everything is falling apart. A programmer should be working in an environment that shows him as much of existing couplings as possible, for his own sake.

I will be recalling this post many times, when arguing about strong vs weak type systems, functional vs object-oriented programming, etc. Beneath any programming language, framework, paradigm, or any other abstraction lies this one basic question - “Ok, but how I will be able to describe and manage coupling in the code? How much of the dependencies will be visible?”

One of the inspirations to write about this topic was Mark Seemann’s post about language features. A lot of resources, like Robert C. Martin’s book “Clean Architecture”, say a lot about managing dependencies, but focuses on the explicit ones. I don’t recall any chapter about “implicit couplings and where to find them”.

What do you think about it? Am I right on this topic or did I miss something essential about it? Was my explanation comprehensive enough? Would you like me to prepare more examples of source code with harmful implicit coupling? Tell me in the comments :)

Sincerely yours,

~Marek