Hi,

I have a board game about a submarine crew that needs to cooperate on fixing failures that are constantly arising to survive for 60 minutes - each turn represents one in-game minute. The most important action a player can do is a repair attempt. If one makes a repair attempt that takes 10 minutes, they fix the failure. If they don’t have so much time and feel brave, they can allocate a lesser amount of time - but quicker the work, the less chance that the fix will succeed. So instead of spending 10 minutes for a fix that has a 100% chance of success, they can decide to spend five minutes for a 50% chance, or even a single minute for a 10% chance of success (each minute adds 10% chance).

I was recently thinking if there is some game strategy that would yield better results on average than other ones - for example, always fixing for one minute, or always fixing for ten minutes. I don’t know enough maths to properly write that problem down, so I’ve just written a script that simulates the game situation and gives me averaged results.

// function that executes a single repair trial and returns its result

const repairTrial = (threshold: number, maxValue: number) => {

const successChance = threshold / maxValue;

return Math.random() <= successChance;

};

// function that executes a strategy - repair trials in a sequence until success and returns accumulated time elapsed in minutes

export const executeSingleStrategy = (threshold: number, maxValue: number) => {

let minutesElapsed = 0;

while (true) {

const repaired = repairTrial(threshold, maxValue);

minutesElapsed += threshold;

if (repaired) break;

}

return minutesElapsed;

};

// math helper function

function getStandardDeviation(array: number[], mean: number) {

const n = array.length;

return Math.sqrt(

array.map((x) => (x - mean) ** 2).reduce((a, b) => a + b) / n

);

}

// genrate given amount of samples and calculate their mean value and standard deviation

export const createStatisticalAnalysisOfSamples = (

samplingAmount: number,

threshold: number,

maxValue: number

) => {

const results = Array.from({ length: samplingAmount }, () =>

executeSingleStrategy(threshold, maxValue)

);

const mean = results.reduce((p, c) => p + c, 0) / results.length;

const standardDeviation = getStandardDeviation(results, mean);

return {

MeanValue: mean.toPrecision(3),

standardDeviation: standardDeviation.toPrecision(3),

};

};

// evaluate mutliple repairing strategies by sampling (getting time elapsed until successful repair) each of them multiple times to see differences in statistical properties between them

export const CompareRepairingStrategies = () => {

return [

createStatisticalAnalysisOfSamples(1000, 1, 10),

createStatisticalAnalysisOfSamples(1000, 10, 10),

];

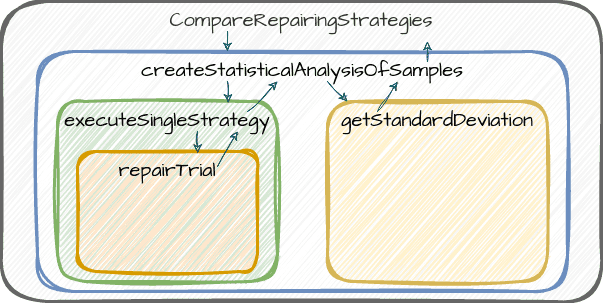

};It was easier for me to think about it as a series of separate stages so I wrote a code that was split into functions that call each other. - it’s an example of simple Procedural programming. In the diagram below there are blocks that represent functions that call each other and pass the data:

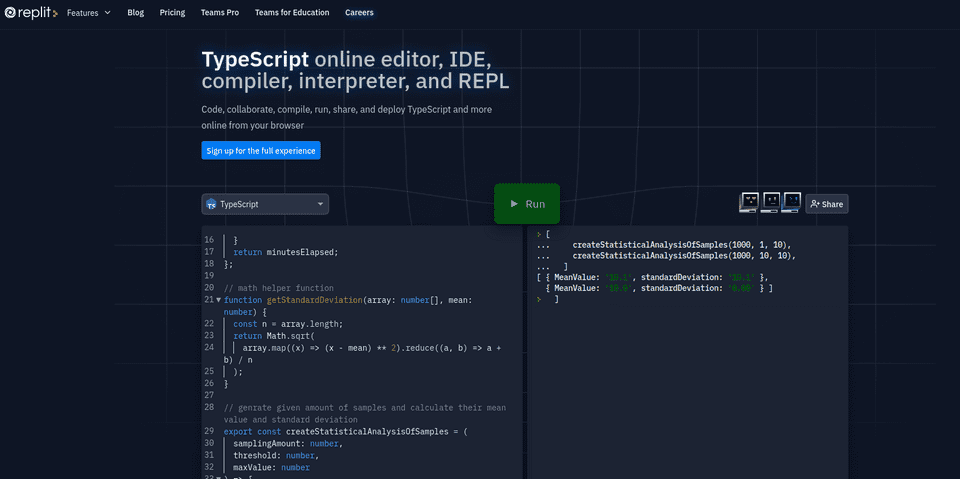

And I’ve got a result in the REPL console - it turns out that it doesn’t matter which strategy you choose, the average time to fix the failure is always 10 minutes.

But then I thought about another thing - in the board game there is a possibility to use a tool to make a repair attempt (if you have it in your equipment) - then the probability of a success is increased by 40% - so with a tool, a one-minute fix has 50% chance and a six-minute fix has 100% chance of success.

I’d like to know if it changes the situation with strategies, but I can’t easily make my script support two different scenarios (with the tool and without the tool). I’ve had to go back and read everything from top to the bottom, realizing that it would require modifications in all functions that I’ve written.

It’s not maintainable code.

Sidenote: Object-oriented programming

A lot of people are convinced that the only way to achieve big, maintainable software systems is to use object-oriented programming paradigm.

Object-oriented paradigm can be a good way to learn some of the concepts about high-level programming and big-scale architecture, but in no way it is the only or the best way to make big and maintainable codebases. There is no such problem that would force us to use object-oriented paradigm and this blog post is written partly as an example of it.

“Separate those things that change for different reasons”

I’m in a situation in which I want to just add a new feature - It’s wrong that I have to wade through all of the existing codebase, add if statements and change all of the function signatures. I would like to have my codebase structured in such a way that adding a new feature would require only creating new functions, not modifying or deleting the old ones.

Separate ‘what’ from ‘how’ - a.k.a. declarative programming

If you have two pieces of source code that you know will be changing separately - it’s better to keep them separate. It will save you from a situation like I’m in right now. Very often you can start by identifying code that defines ‘what result do you want to get’ and ‘how do you want to compute it’. You can make such a separation almost always, regardless of what domain you are working with. Example from my script:

- What? - “I want to see the average time it takes to fix a failure for each of the different game strategies to see if one of them is quicker”

- How? - “You can average fix time for a given strategy this way - simulate fix attempts (with simulated dice roll) until it eventually succeeds and store time elapsed. Repeat all that 500 times and then average the numbers you got from simulations.”

Functions that implement the ‘how’ part (for example - dice roll, or single simulation of fixing failure) won’t need to change anymore if I decide to add a new feature to the program. A function that calculates average and standard deviation won’t have to change ever again.

That way, future maintainer won’t have to read the whole codebase just to be sure that they won’t break anything while adding a new feature.

“Declarative programming” is not only the “what” part because computers can’t (yet) decide on their own how to achieve the results that they were asked for. Declarative programming consists of both “what” and “how” parts but fundamentally separated. The “how” part is often called ‘an engine’ - like a browser engine, game engine, react engine, etc.

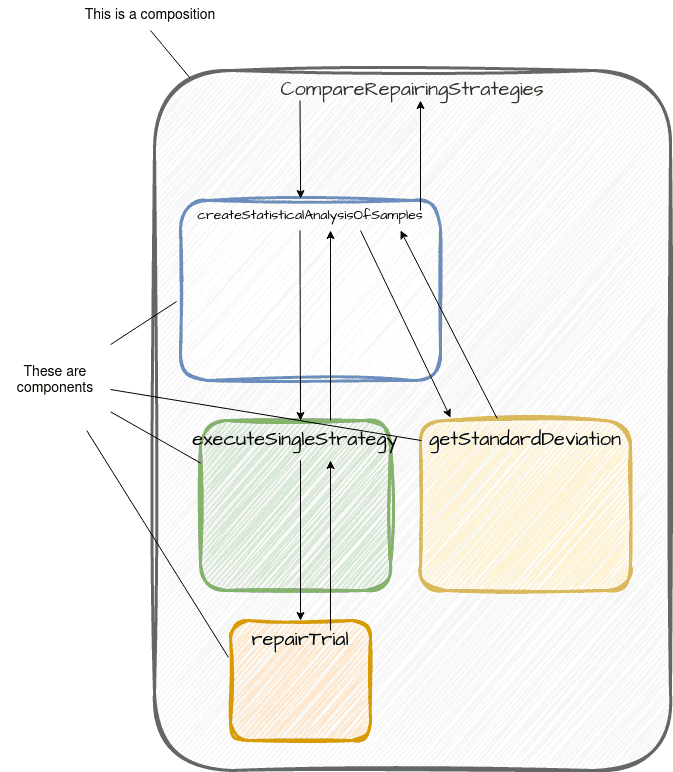

Component - composition pattern

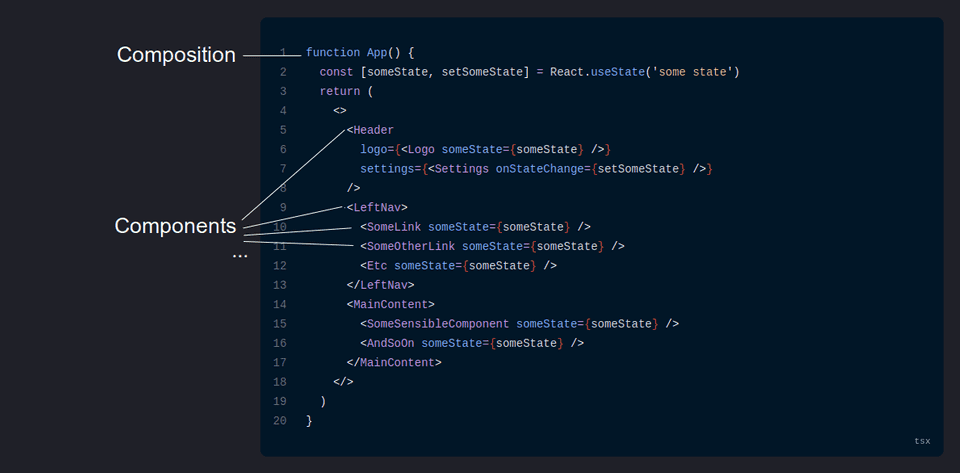

So the pattern is to separate “what” from “how”. Our “what”s will be called from now on “compositions” and “how”s will be called “components”. Let’s refactor the code:

import { createStatisticalAnalysisOfSamples } from "./mathTestUtils";

// create a function that executes a single repair trial and returns its result

const createRepairTrial = (threshold: number, maxValue: number) => () => {

const successChance = threshold / maxValue;

return Math.random() <= successChance;

};

type CreateSingleStrategyExecutionArgs = {

repairTrial: ReturnType<typeof createRepairTrial>;

trialDuration: number;

};

// create a function that executes a strategy - repair trials in a sequence until success and returns accumulated time elapsed in minutes

export const createSingleStrategyExecution = ({

repairTrial,

trialDuration,

}: CreateSingleStrategyExecutionArgs) => () => {

let minutesElapsed = 0;

while (true) {

const repaired = repairTrial();

minutesElapsed += trialDuration;

if (repaired) break;

}

return minutesElapsed;

};

export type TestEnvironment = {

maxRepairingTime: number;

samplingAmount: number;

repairStrategies: number[];

};

// Composition - evaluate mutliple repairing strategies by sampling (getting time elapsed until successful repair) each of them multiple times to see differences in statistical properties between them

export const CompareRepairingStrategies = ({

maxRepairingTime,

samplingAmount,

repairStrategies,

}: TestEnvironment) => {

const strategyTests = repairStrategies.map((repairDuration) =>

createStatisticalAnalysisOfSamples({

samplingAmount,

getSample: createSingleStrategyExecution({

repairTrial: createRepairTrial(repairDuration, maxRepairingTime),

trialDuration: repairDuration,

}),

})

);

const strategyResults = strategyTests.map((test) => test());

return strategyResults;

};I’ve refactored ‘component’ functions in my script to accept other functions they use as arguments. The concrete implementation that will be used will be decided outside of them. Regardless of that, the data flow of the app remained the same, only the decision about the chosen implementations has been pulled all the way up to the ‘composition’ function which became something known also as Composition Root.

Components can be now joined with each other (by providing arguments and extracting return value) and this act of joining is executed in a composition function. Because of that, it’s not needed anymore to ‘drill’ some new arguments through multi-layered function calls, nor to read everything one by one to get to the single step that interests you.

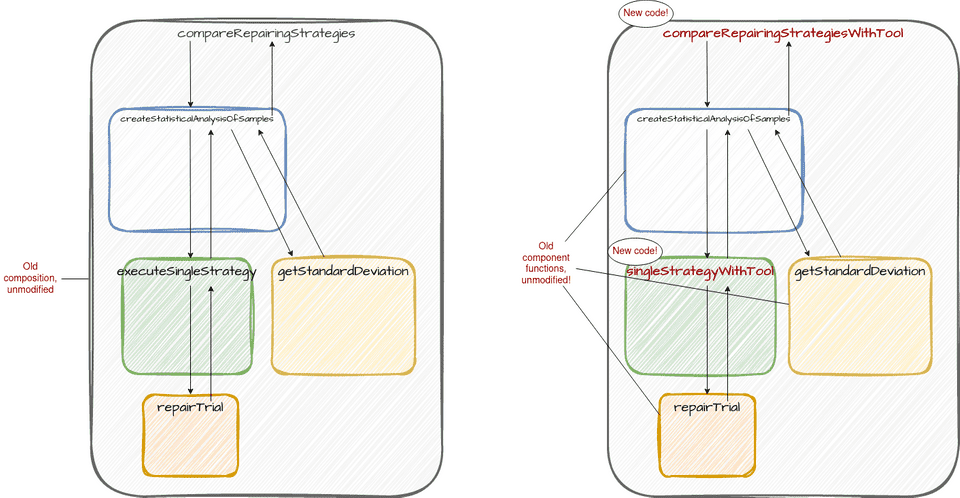

Now, adding new functionality to this program - whatever level it would be - requires only adding a new composition (which would re-use most of the already-written components) and optionally adding new components if we need some new kind of computation step.

In my script it will look like this - just add these lines of new code:

// new component

export const createSingleStrategyExecutionWithTool = ({

repairTrial,

repairTrialWithTool,

trialDuration,

}: CreateSingleStrategyExecutionWithToolArgs) => () => {

let minutesElapsed = 0;

let toolAvailable = true;

while (true) {

const repaired = toolAvailable ? repairTrialWithTool() : repairTrial();

// tool is always single-use

toolAvailable = false;

minutesElapsed += trialDuration;

if (repaired) break;

}

return minutesElapsed;

};

// new composition

export const CompareRepairingStrategiesWithTool = ({

maxRepairingTime,

samplingAmount,

repairStrategies,

}: TestEnvironment) => {

const strategyTests = repairStrategies.map((repairDuration) =>

createStatisticalAnalysisOfSamples({

samplingAmount,

getSample: createSingleStrategyExecutionWithTool({

repairTrial: createRepairTrial(repairDuration, maxRepairingTime),

repairTrialWithTool: createRepairTrial(

repairDuration + 4,

maxRepairingTime

),

trialDuration: repairDuration,

}),

})

);

const strategyResults = strategyTests.map((test) => test());

return strategyResults;

};Diagram that shows our codebase - new composition alongside old (totally umnodified) one:

Now, when a future maintainer would like to know “what this feature X does?” he would be able to open the single composition function, see steps (components) used to get the result and by function names roughly deduce what it does. If he then decides to check “how is dice roll being calculated?”, he will be just one ‘go to definition’ step away, instead of four jumps, or worse, four jumps going through the whole codebase, dependency injection framework, etc. You can’t visualize your whole codebase at once in your head, so don’t write it in such a way that it’s required every time you want to make a single change.

Open-closed principle

And that’s why there is a saying that “Software entities should be open for extension but closed for modification” - This principle helped me recognize that adding a feature should consist mainly of adding a new source code, not modifying all functions already existing in a codebase. One new feature means one new composition and optionally new components if they are needed. Old ones shouldn’t change whenever something happens in the codebase. If we avoid modifying old code during our ‘typical’ work (of course it’s still important to modify it during refactoring, deleting features, fixing bugs, etc.) we help ourselves by:

- introducing fewer regression bugs

- having an architecture that allows developing any number of variants for each part independently without collapsing to ”

ifChristmas trees” and spaghetti code - having a codebase that is easier to reason about and navigate

Didn’t I read about this before?

It’s not a new idea in any way. React (a frontend framework) uses this paradigm to build web applications with reusable components. Each react component can itself be also a composition of children components.

In fact, after JSX transpilation (without these angled brackets, which are being transpiled into function calls), the source code that uses react start looking the same as my source code.

Can it be further improved?

It’s still a throwaway script, in big codebases source code doesn’t look that way. It would have more standardization or some system to manage components (like dependency injection framework in OOP). It could be also refactored to have all components operate on simple data and composition would manage things like data splitting, filtering, and mapping. Moreover - functional programming frameworks have tools that could improve developer experience in the component-based architecture. There are mathematical structures that allow us to derive information or give some guarantees about how components will behave, or how they can be joined. Don’t even get me started on monads 😉. You can think about React as such a tool - a tool to improve the manageability of a component-based software system. And more libraries are being created right now that aim to allow programming in this paradigm in other domains, for example: https://usegpu.live/docs/reference-live-@use-gpu-live

Sincerely,

~Marek